Grocery costs continue to rise nationwide in tandem with inflation. As the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) notes, food prices were more than 10 percent higher in June 2022 than in June 2021, leading to spikes in price tags on foods like bread, eggs, and meat.

In response, consumers are seeking savvy solutions that are kind to their bank accounts.

One of the smartest ways to stretch your grocery store dollar is to figure out how to decode those notoriously misunderstood food labels.

It’s a way to avoid preemptively discarding unspoiled food. A 2011 Food Marketers Institute (FMI) study found that many Americans prefer to be safe rather than sorry in deciding whether their store-bought food is still good to eat. The study found that 91 percent of participants said they “at least occasionally” discarded food past its “sell by” date, out of safety concerns; 25 percent reported that they “always did so.”

Those attitudes may help explain why an estimated 30–40 percent of the nation’s food supply goes to waste each year, according to a study published by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2014.

To put that in context: According to the 2014 USDA study, an estimated loss 133 billion pounds and $161 billion worth of food was lost 2010.

If fattening your wallet isn’t enough incentive to educate yourself about what the dates on food labels mean, consider the environment. Inger Andersen, the executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, says food waste is a “major contributor to the three planetary crises of climate change: nature and biodiversity loss, pollution, and waste,” per the 2021 UNEP Food Waste Index Report.

Why Food Expiration Dates Are So Confusing

You’re not alone if you’re uncertain about what different food labels mean. A 2007 survey of U.S. adults published in the Journal of Food Protection shed light on how misunderstood these terms are by the general public.

A snapshot of the findings: Fewer than half the study’s participants could correctly define the “sell by” date, and one-fourth had the misconception that this date indicates the last date recommended for safe consumption.

Another big reason for the confusion is that there’s “no federal regulation and no standard definition” when it comes to food labels, says Dana Gunders of Truckee, California, the executive director at ReFED, a national nonprofit dedicated to ending food loss and waste.

She is among the leaders pushing for the government to adopt a uniform policy for product dates. At present, laws vary by state, which contributes to the confusion.

What Different Food Expiration Dates Mean

The truth is, common labels like “best by,” “use by,” and “sell by” stamped on your food items aren’t safety dates, says Amy Shapiro, RD, the founder and director of Real Nutrition, a private practice in New York City.

Manufacturers use food product dating to advise consumers on when the food they’re purchasing is of the highest quality. “Best-by and use-by dates are really designed for the look of the product and the palatability of the product,” says Bill Marler, a food safety attorney in Seattle.

Here is a simple list of common date conventions on food labels and what they mean, according to FSIS.

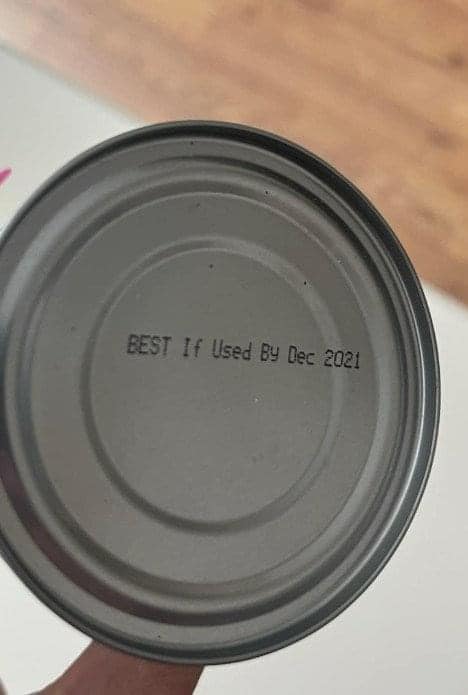

Best if Used By/Before

If your food has a “best if used by/before” label, this notes when a product will be of the highest quality or flavor, per the agency, and does not mean it’s no longer safe to consume after that date (it might just not taste as good). This label is used for all food categories, including frozen, refrigerated, canned, and boxed products.

Use By

A use-by date is “the last date recommended for the use of the product while at peak quality,” according to FSIS. Like the above labels, it does not mean the food is no longer safe to consume after that date, except in the case of baby formula (more on that below). This label is typically reserved for foods that are highly perishable, like meat, dairy products, and ready-to-eat items.

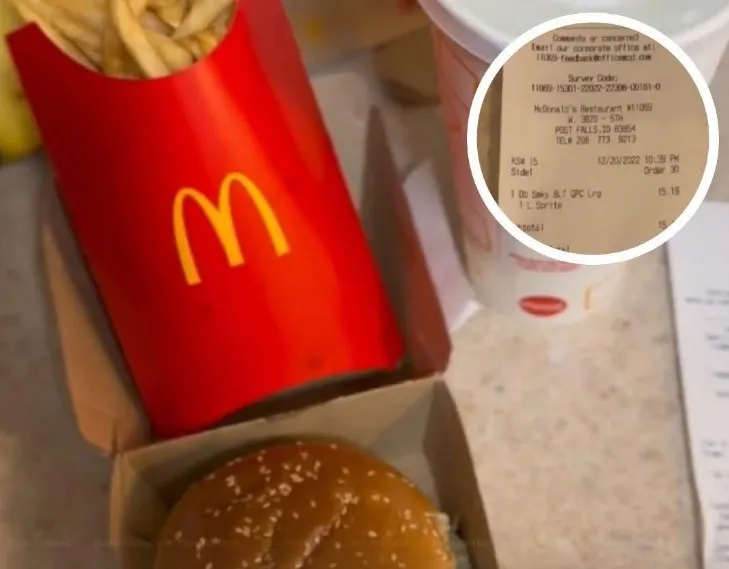

Sell By

A food product’s sell-by date refers to how long it should be on sale in stores and is for inventory management. You can still consume food after this date.

How to Decide When to Toss Your Food

So, do you need to dispose of food once these dates have come and gone? The answer is a resounding no — that is, unless the item is showing signs of spoilage. Besides funky smells, other noticeable signs of spoilage are changes in “color, consistency, or texture,” per the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

As mentioned earlier, baby formula is an exception, and Shapiro notes it should not be purchased or used after the use-by date. It’s the only food item that requires a use-by date, enforced by the FDA.

“Until that declared date, the infant formula will contain no less than the amount of each nutrient declared on the product label and will otherwise be of acceptable quality,” according to the federal agency.

As for pantry items, you don’t have much to worry about. The date on the can refers to its peak quality, but it will last much longer. The USDA advises that low-acid foods (like canned tuna or vegetables) will “keep their best quality” for two to five years. On the other hand, high-acid foods (like canned pickles and fruit) tend to last for 12–18 months.

In some cases, canned foods may last longer. “If cans are in good condition (no dents, swelling, or rust) and have been stored in a cool, clean, dry place, they are safe indefinitely,” notes the agency.

And finally, a smart option is to freeze your food. As long as you do so right away — when it’s at its highest quality — meats, casseroles, soup, and frozen dinners will stay safe “almost indefinitely,” per the FSIS, since bacteria can’t grow in frozen temperatures.

Should You Be Concerned With Foodborne Illness?

There is one benefit to being overly cautious about heeding the information on food labels, and that’s the potential to avoid bacterial infection. Why? “The longer something’s around — if it has bacteria on it — the more likely it is that the bacterial growth will be such that’ll make you sick,” says Marler.

“There’s a certain infectious dose that’ll do that and it varies from bacteria to bacteria,” he continues.

He deems listeria — a foodborne bacterial illness — ”much more problematic,” because unlike most bacteria, it “grows well at refrigerator temperatures.” That means “the longer you keep it in your refrigerator, the more likely it is that it’ll reach an infectious dose high enough to make you sick,” he says.

Marler notes that while food labels aren’t designed for food safety, it’s good to pay attention to them in the unlikely case of listeria contamination.

Even so, if the product’s already contaminated, further refrigeration won’t help.